Daptar (दप्तर) – A Digital School Bag

A distraction-free, safe & adaptive educational device.

दप्तर - School Bag in Marathi (an Indic language)

tl;dr:

I’m building Daptar, an adaptive educational tablet that will be designed specifically for curriculum-based learning. It will function as a textbook, notebook, and exam sheet, and will transform into a full computer for skill-building.

The device will support handwriting-first input to aid deeper thinking and comprehension. It will be physically safe, with a low-strain display and no blue light, and will include robust parental controls. My goal is to make digital learning accessible, focused, and future-ready for every child.

If you’re a designer, engineer, or educator excited by this vision, I’d love to collaborate—let’s build it together.

Last year, I met my 10-year-old twin cousins for the very first time when they visited my parents. I was curious about them—they came from the same small village where I spent the first nine years of my life. I watched them closely, wanting to compare them with my nieces growing up in big cities. Like my nieces, they were glued to my mother’s mobile phone—but when I asked, they excitedly showed me worksheets they had found on the internet. During the pandemic, with only one teacher responsible for multiple classes at their government school, free online resources had become their main source of learning. It was heartening to see their curiosity and resourcefulness, but bittersweet too, as it reminded me how critical access to education—and later, to digital resources like the internet, YouTube, MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses), and devices—had been in shaping my own journey.

Most of the skills I use today were self-taught through these digital tools rather than formal university classes. Thinking about this, I felt compelled to gift them a tablet, as they currently relied on their father’s phone during the short time he was home. But just before I could make the purchase, I paused. I remembered how one of the twins, full of excitement, had led me to a website that claimed to predict your death. It wasn’t just a passing moment; it made me realize how easily unsupervised access could expose them to harmful content. With their parents’ limited digital literacy and time, a well-meaning gift could unintentionally open the door to risks. It was a sobering realization that has stayed with me ever since.

Over the past five years, this question—how to shape learning for the next generation—has been constantly on my mind. More specifically, I’ve been reflecting on the role that electronics and digital resources play in that journey. My own life experience has convinced me that these tools are no longer optional—they are essential. They ignite curiosity, enable self-driven learning, build critical digital literacy, and prepare children for a future where almost every job will involve working with or around computers.

Today, we are witnessing an explosion of edtech applications. With the rise of LLMs and progress toward AGI, a growing number of startups are developing AI-powered solutions for students, teachers, and schools alike. While these innovations are exciting and carry immense potential, they often overlook a crucial foundation: the underlying infrastructure. Reliable access to computers, mobile devices, and child- and learning-friendly operating systems is vital to ensure these tools are truly effective. Without addressing accessibility and the systemic challenges tied to this core infrastructure, the benefits of technological advancements will remain out of reach for the majority who need them the most.

The Accessibility Gap

Let’s acknowledge a basic truth: access to digital learning is profoundly unequal. Broadly, there are three Indias in this context:

India One: Where children have their own devices, reliable internet, tech-savvy parents, and access to curated digital learning experiences.

India Two: Where parents have smartphones or laptops, but children only get limited access—often due to device sharing or concerns about distraction and screen time.

India Three: Where even a basic mobile phone is a luxury, and education often stops at the school gate.

When Devices Are Present, They’re Rarely Designed for Learning

Even when devices exist, they’re not designed for learning. Even in homes that do have devices, the experience is far from ideal. A child borrowing a parent’s smartphone for online classes is a compromised learning setup. It’s distracting, unstructured, and often unmonitored. Most smartphones are made for entertainment, not education.

Parents are rightly concerned: exposure to addictive content, social media, and unfiltered internet can do more harm than good. So, access becomes restricted or highly controlled. What’s left is a broken learning loop—where a device exists, but the child doesn’t fully benefit from it.

Now let’s look at computers. According to a 2018 NSSO survey, only 11% of Indian households owned a computer. Tablets made for kids? Practically nonexistent.

The conversation around digital education often assumes that if you just put content online, kids will learn. But access to content is meaningless without access to the right device, at the right time, in the right context.

Why Previous Efforts Didn’t Stick

Initiatives like One Laptop Per Child and Aakash Tablet tried to address the issue.

One Laptop Per Child (OLPC) is a nonprofit initiative launched in 2005 to provide low-cost, rugged laptops (with a $100 target price) to children in developing countries, aiming to improve education through technology. However, high costs and a lack of teacher training led to underuse and limited educational impact. The organization has been accused of simply giving underprivileged children laptops and “walking away”.

Aakash Tablet was an Indian government-backed project launched in 2010 to deliver ultra-low-cost ($35 - ₹2,500) tablets to students for digital education. It struggled due to poor hardware quality, manufacturing delays, lack of technical support, and weak integration with educational programs, eventually losing public trust.

A device that enables ‘studying’ is built differently from one designed for ‘reading’. You can read a novel. But when it comes to studying, say physics, a student ought to be able to read on the device, make notes on it and work out answers to a problem. “Aakash is a disaster,” says a newly retired vice chancellor of one of the largest technological universities in the country.

“Without taking a long-term view of the end use of the device…it will remain ineffective.” Ashok S Kolaskar, former vice chancellor of Pune University and KIIT University in Bhubaneswar, calls the content that is being digitised by the MHRD “19th century textbooks in audio and video format.”

I worked on Aakash myself and saw its limits firsthand. The challenges went far beyond hardware—it was a mismatch of intent and implementation.

Devices were distributed without considering real classroom needs. No guidance. No ecosystem. No integrated curriculum. No thought to long-term health or behavioral impacts. And that brings us to the darker side of today’s devices.

The Dangers of Current Devices

Back when I was growing up, around 2001–2002, in India, digital spaces were quieter—fewer apps, fewer distractions. Kids today are navigating a very different world: infinite scrolls, algorithmic dopamine loops, and overwhelming information flows. The risks are real and growing:

Shorter attention spans

Rising anxiety and mood swings

Sleep issues

Cognitive strain from multitasking

Physical impacts like eye fatigue

So yes—children need digital access. But not in its current form.

The Need is Clear—But What’s the Path Forward?

At this point, the need feels self-evident. The solution, however, is less clear. Meaningful digital access remains a distant goal for many.

What If we make Devices Integral to Education?

What if we rethought the device—not as a luxury or extra, but as a core educational tool? What if the device replaced the school bag?

Our education system still revolves around paper: textbooks, notebooks, exam sheets. Meanwhile, computers are introduced only as a subject—too late, too limited.

A purpose-built device could take the place of textbooks, classwork notebooks, homework, and exam answer sheets. It could evolve with the student, unlocking more functionality as they grow. And because it’s central to learning, it levels the playing field—especially for “India 3.”

Enter Daptar: a new-age digital tablet device that replaces the need for paper while bridging gaps in accessibility and digital literacy.

What Daptar Aims to Be

This can’t just be another repackaged tablet. Daptar needs to be education-first, built specifically for how children learn and grow. It must:

- Function as a digital textbook, notebook, and exam sheet - all in one

- Transform into a full-fledged computer when needed - for skill-building in coding, design, CAD, video editing, and hobby electronics - especially when connected to an external screen/TV and used in the monitored environments of home and school

- Be safe and secure, with strong parental controls and a distraction-free learning environment

- Grow with the child—unlocking age-appropriate features and tools over time

- Prioritize cognitive development and protect physical health

- Handwriting-first interaction with a pen. Why handwriting? Because studies consistently show it strengthens memory, comprehension, and critical thinking.

- Safe, low-strain displays without blue-light overload

- Serve as a safe foundation for introducing emerging technologies like AI in education

- Adapts as children grow—supporting creativity, experimentation, and technical skill-building

Families already spend ₹5,000–₹6,000 annually on books and notebooks. Over a few years, this budget can be redirected—making Daptar an economically sustainable option.

Fixing What’s Long Been Broken

- A Future Without Heavy School Bags

And let’s not forget a very real, everyday burden: the school bag. Even first graders carry bags heavier than their backs can handle. We’ve had to invent guidelines like “bags shouldn’t exceed 10% of body weight”—a patchwork fix to a solvable problem.

Daptar changes that. No more textbooks. No more notebooks. No more paper. Just one light, versatile device that holds everything a student needs.

- Connecting the Physical and Digital—Intelligently

Today’s learners juggle QR code scanners and OCR (image scanning) apps just to make content created in the physical world usable. It’s clumsy and inefficient.

Daptar would remove that friction entirely. All materials—books, assignments, notes—are born digital, interactive, and intelligently organized. No need to “scan” answers to evaluate with AI; everything happens within a cohesive ecosystem.

Development Plans

I am building Daptar from the ground up—custom hardware and a purpose-built operating system designed specifically to support the kind of educational experience I’ve outlined above. This isn’t about repurposing tablets or tweaking existing platforms. It’s about rethinking what a digital learning device should be.

Go-to-Market Possibilities (Initial GTM Options)

I am exploring a few potential paths to introduce Daptar into the real world:

Direct-to-learners (B2C) - Independent learners, students of the NIOS curriculum and growing Home-schooling community

Partnership with an independent school or alternative curriculum framework

Paper replacement device for non-school environments to help families familiarize with digital tools in a safe, educational context

Each path has trade-offs. For instance, working with a single school might limit scale due to systemic requirements like paper-based exams. These are open questions—and the answers will likely emerge through experimentation and community feedback.

Progress So Far

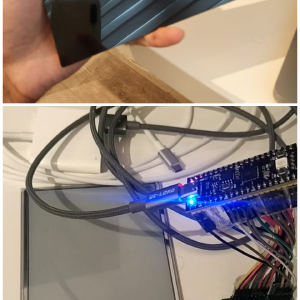

I’m currently prototyping both the hardware and the operating system. A functional prototype is on the horizon—one that can demonstrate the core philosophy in action. It’s still early, but the foundation is taking shape.

On the hardware side, I’m prototyping with NXP and Rockchip based platforms with custom hand-writing controls & safe screen options like ePaper, trans-reflective LCDs.

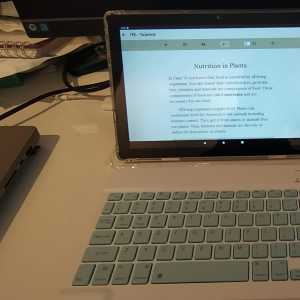

For the operating system, I’m taking a Chrome OS-inspired approach to run applications built with web technologies, which have a lower development complexity and are widely known. On the application side, significant work remains to digitize the Indian curriculum. I’ve been developing AI-powered tools to speed up content digitization. I also create demos to illustrate what’s possible with proper digitization—Daptar Digital is one example. Previously, through Daptar’s textbook reader, I showcased a textbook reading platform with first-class AI assistant integration.

Experiments with displays.png

Experiments with displays.png learning, tinkering, and a glorious mess

learning, tinkering, and a glorious mess Handwriting Tech - Work in Progress

Handwriting Tech - Work in Progress Linux processor experiments

Linux processor experiments Off the shelf reference

Off the shelf reference

Who Am I?

If you’ve found your way to this article — perhaps by a stroke of serendipity (though it’s unlikely you landed here through Google) — let me introduce myself.

I’m Prashant Aher. I am a software engineer by profession, but more than that, I am a builder at heart. Currently, I live in Amsterdam, Netherlands. I have a professional experience of 11 years, during which I’ve worked across the entire technology stack — from systems engineering to web, mobile, and desktop applications, UI/UX design, and cloud technologies. Every project has been a part of my journey in building meaningful, impactful products.

Since 2013, I’ve been creating utility applications for web and mobile platforms, reaching over 2,00,000 users around the world. For the past one year, I’ve been on an exciting new path: bringing Daptar to life. To make this vision a reality, I immersed myself in the world of electronics and manufacturing — learning everything from designing and sourcing to assembling and testing hardware.

With my diverse technical background and hands-on experience, I’m confident in my ability to execute the full technical vision behind Daptar — and beyond.

An Open Call for Collaboration

This is not a solved problem. And it’s not something one person can build alone.

I’m actively looking for technical collaborators—people passionate about education, hardware, software, and design—to join and co-create.

This project touches several first-principles challenges:

How do we digitize textbooks meaningfully, not just scan PDFs?

Can we design open API specifications for interoperability across educational organizations?

How do we build novel computing interfaces—especially around handwriting input and next-generation displays that support calm, focused learning?

How can we design and build system software—such as linux desktop environments, application sandboxing frameworks, and mobile device management (MDM) tools—to create a safe, education-focused computing experience for children?

If any of these questions excite you, you’re exactly who this project needs.

If the prototype proves successful, in future, I hope to raise $300,000 USD (~₹2.5 crore) to bring 1,000 units of Daptar to life. Right now, more than funds, I’m looking for co-creators: engineers, designers, educators, and curriculum experts.

If this vision resonates, let’s talk.

References

State of Indian Digital Education

- Oxfam India’s Digital Divide in India Report

- Azim Premji University’s Myths of Online Education Paper

- Central Square Foundation’s EdTech Working Paper

- Decoding ASER 2023: Understanding the Educational Landscape of India (2024)

Commentaries/Coverage on above sources

- World Economics - How local innovations in India are helping to bridge education’s digital divide

- 23% of urban population has access to computer, only 4% in rural - Survey

- India’s COVID-19 divide in digital learning

Previous Efforts

Harms posed by mobile devices

- WHO - Teens, screens and mental health

- Digital multitasking and hyperactivity: unveiling the hidden costs to brain health

- How Blue Light Affects Kids’ Sleep

- Attention, Media Use, and Children - A guide from the experts on digital media’s effects on youth attention

Importance of Hand-writing

- Why writing by hand beats typing for thinking and learning

- Why writing with your hands is better for the brain

Others